»The malaise of despair is better cured with decadence than with providence…« When D. Kaufman was Jean-Jacques Rousseau fellow at Akademie Schloss Solitude, he wrote this beautiful insight into a procrastinators mind.

I wake to the stretching and snapping sound of unstrapping the bounding plastic wrap of a pack of red Gauloises and then tend to the window for a smoke. My agoraphobia produces uncontrolled trembling at the open space in the view spread out in front of me. I see a forest of some sort, and grass, overlooking nothing. I smoke the cigarette swiftly, like, I would imagine, a mental patient in a closed ward would, one getting used to his new schizophrenia medication. A twisting molecule appears in my mind’s eye as I think of cars and concrete and underground trains and being nudged by elbows in Paris by people who consider me décor, and then I relax a little. The view from the window remains. I’m in Stuttgart. The view is the rear of the Schloss Solitude. I squeeze my retina to make sense of the view to see old folk dragging themselves while holding what appears to me like decapitated ski poles; they are hoping, perhaps, to end their misery by abruptly slipping on the frozen pavement and severing their spinal cord from their medulla oblongata. A distinct, barely noticeable, smell of dung comes and goes haphazardly. A red Porsche is parking, rather criminally, near the restaurant (and café, as the sign informs me), and I wonder: how can the tackiness of Rococo withstand such a scoffing derision that comes with one’s anxiety about his own mortality.

To properly ponder this inquiry I procured a bottle of rosé Moët & Chandon at Galeria Kaufhof — a mild bourgeois department store — with the money that I received as stipend; money that I’m supposed to be prudent about, but, and unfortunately, the malaise of despair is better cured with decadence than with providence. The champagne is now chilled on the windowsill, overlooking repressed suicidal old folk, red Porsche in parking misdemeanor, said restaurant (and café). On the inside I reside; two rooms, bedroom and studio. Studio holds, I was informed, a fold-out sofa, as of yet unexplored, in red. A large writing desk, office chair, small dinner table. Bedroom has a single bed covered in white sheets, closet. The toilet and washroom are clean and comfortable. There’s hot water in opulence. To leave towards town one has to either order a taxi or twiddle one’s thumb and wait for the consistently late 92 bus at the Solitude stop, nearby Haus 3, adjacent to Haus 2 (where I reside), which faces the Schloss itself; a late Baroque palace, which, I guarantee you, is absolutely locked.

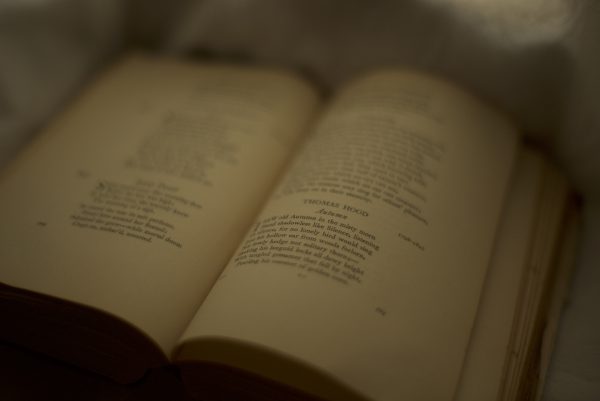

I haven’t left. It’s too cold. I’m still in the studio looking out the window while listening to Radio Orfey, sauced. The radio waves are broadcasted to this temporary abode directly from Moscow. The incessant chatter of the radio jockey eventually ceases as the broadcast turns from breezy to melodramatic, as the day turns to night, as I do when sipping Moët and looking out my window, as the temperatures fall, and then collapse, to a witch’s teat, and then to a bitter, spiteful, windy cold. But, even though the universe is very evidently in the midst of a murderous wintery February, I happen, as if out of spite, to hold Autumn, the Thomas Hood poem – where my thumb arbitrarily stuck as I absentmindedly flicked through a disintegrating Oxford Book of English Verse, a 1943 reprint – where, at the beginning of the closing stanza of said seasonal poem on page 771 informs me, perhaps teasingly, that:

Alone, alone,

Upon a mossy stone,

She sits and reckons up the dead and gone

With the last leaves for a love-rosary,

Whilst all the wither’d world looks drearily,

Like a dim picture of the drownèd past

In the hush’d mind’s mysterious far away,

Doubtful what ghostly thing will steal the last

Into that distance, gray upon the gray.

I purchased this book when I was seventeen-years-old and on a memorable day. I had a brother once, actually too not long ago, as he died just four months ago. He was a sculptor, he never married, and, as a matter of fact, he was a very special guy. He once decided not to attend obligatory military service, and, consequently, military police arrived at his doorstep, swiftly pulled out his shoelaces from of his shoes — lest he renounce his own life while relieving himself in the lavatory prior to departing — and took him to what I can only imagine was a harsh military prison. I write that I can only imagine because he never indulged any information on said event, and, in any case, he was not the candid type. He was never quite the same since then. The day that he was released from prison, my father and I went to take him back home, but he declared that he and I will go directly to town, from prison, to visit some of his favorite used bookstores. This is where I laid eyes on the old bound Oxford. I immediately requested it should be fetched from the top shelf, without even having able to read the book’s title. It was the cover I suppose – a sort of venerable, crumbling, old dark blue – that got me.

I possess some sort of a for crumbling things. Most of the things I’ve owned have crumbled by now, very much so and in many senses. But that is not entirely true. I leave books behind as they are too heavy to carry, but I consider them still mine. I don’t have so many things; everything I own is here. I only own what fits in my leather duffle bag. I am not the materialistic type, but all my things are fine. I own two pairs of very good Italian shoes, a cashmere coat, a decent jacket, fitted suit trousers, and two quite adequate pens (upscale but not nouveau riche, they are heavy and bleed ink on the page sufficiently well). Most of the rest of what I own belonged to my grandfather, some of his clothes, his watch. I am now wearing his vest. I like wearing it when I go to the library, even though I’m not currently in a library, but in my studio in the Akademie Schloss Solitude, which is, I’m coming to realize, very different than the labyrinth of Pompidou—my usual habitat. My grandfather’s vest is beautiful, it’s the one that I’m still wearing while drinking champagne in Stuttgart. Though, it’s not vanity that makes me wear it to the library, but rather that I have some of the hereditary librarian in me, and I believe that one should respect the book he or she is reading and dress well for the occasion, as reading a book is an occasion, and one that I celebrate, doubly so because reading seems sometimes as routine, but it’s nothing but, it brings such great joy to me, I think the little I can do is dress well while I do it. I also think that one should always read with a writing instrument in hand, or one nearby, as it is the only serious way to read anything, along with some paper nearby, as I do not subscribe to idea that one should scribble notes at page margins, unless one has an absolute immortal idea equal to that of the words that already grace what is soon to be a littered page, and those sort of ideas, it’s needless to say, are rare. Generally speaking one should be content with a dedication at most. This copy of the Oxford has a dedication, in German of all languages, and dates to 1945, it reads »Viel Glück.« Yes, Good Luck.

My stomach informs me that I should eat. I sometimes forget to eat, especially when I write. Both the chicken and avocado in the fridge are already dead and will patiently wait a little longer while these platitudinous words vacate whatever subconscious whim that happens to make my hand move, and, in any case, I doubt that they will produce any equivalent of a Proustian madeleine effect of any kind.

Thomas Hood still stares at me, it’s still Autumn at Hood’s, here it’s still February, and it goes on:

O go and sit with her, and be o’ershaded

Under the languid downfall of her hair:

She wears a coronal of flowers faded

Upon her forehead, and a face of care;—

There is enough of wither’d everywhere

To make her bower,—and enough of gloom;

There is enough of sadness to invite,

If only for the rose that died, whose doom

Is Beauty’s,—she that with the living bloom

Of conscious cheeks most beautifies the light:

There is enough of sorrowing, and quite

Enough of bitter fruits the earth doth bear,—

Enough of chilly droppings for her bowl;

Enough of fear and shadowy despair,

To frame her cloudy prison for the soul!

I tend to agree with the poet here. This is notable because I don’t agree often, on principle. I am a contrarian, and I will save you the spiel of the benefits of contrarianism to producing dialectic and reduce this tendency to something, hereby of great magnitude, that happened during my childhood, something that I can’t quite recall, but I’m sure that with a good Freudian analyst I could somehow dig down deeply and finally expose. I am doubtful this would alleviate any of the symptoms of my anxiety, but would perhaps help the Freudian analyst procure a red Porsche, like the one still shining outside, from Porscheland, Stuttgart.

It occurs to me that I’ve taken Joyce’s lines from The Dead too much to heart, and that I am scrawling these words in order to avoid writing what I’m supposed to be writing, something that at the moment I sneer at and mock the sound of my own voice reading it while I read it. I am contemplating how to further avoid the obligatory solemn writing and remember that I’ve promised my aunt that I will call her. She calls me Dushka which kind of means »sweetie,« but it is also an endearing name for an old machine gun, and I am not sure which one she refers to. I elliptically entangle myself in these insoluble questions and decide to attempt and find a giant who’d welcome this sneering nonsensical stream of (rather docile) consciousness on his shoulders so I could resume the aforementioned more somber work, and, behold, in Summa Theologica, Section 6, where Thomas Aquinas – now victim-cum-giant whose shoulders are surely wide enough for this unwise escapade – asks: »Whether endurance is the chief act of fortitude?« He meditates an answer, »For virtue ‘is about the difficult and the good’ (Ethic. ii, 3). Now it is more difficult to attack than to endure. Therefore, endurance is not the chief act of fortitude.« He goes on syllogizing Aristotle, (Ethic. iii, 9), that »fortitude is more concerned to allay fear, than to moderate daring,« and so on and so forth reflective thoughts. Concluding that as one must endure to be courageous, rather than go to a spiritual onslaught – to put forth in a reductionist yet straightforward way – so perhaps the old folk outside have a point after all, maybe I should wait a bit, maybe I should join them outside in the freezing cold, maybe I should endure a bit more.