»If things are already going well, there’s no need for hope.«Polly Gregson

What does a future archive tell us about the present? What different perspectives can be drawn around future scenarios of our ecological environment and its influence on our social lives? Artist Polly Gregson – based between Cornwall and France – examines a future world through the format of a possible archive. Future Relics:Catalogue #1 collects fictional everyday objects, calculations, and other testimonies from a distant time which can be traced back to the present awareness of ecological issues in a more or less distinct way.

Judith Engel: Future Relics:Catalogue#1 seems to circulate between fictional writing, science-oriented research, futuristic speculation, and ecological disasters. I found it simultaneously humorous and frightening that the vocabulary of a possible future dystopia is more or less represented through an image-based archive. What brought these topics to your attention?

Polly Gregson: The thread of ideas tied its first loop round Rob Nixon’s text Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. His comparisons between Hollywood blockbusters, climate change and the destructive relationship between rich and poor communities had me seeing links and graphs everywhere, pushing and pulling social and environmental phenomena to see which bits were attached. From there, it’s mostly been an interest in science-fiction and a despair for science-reality that has generated these words and objects.

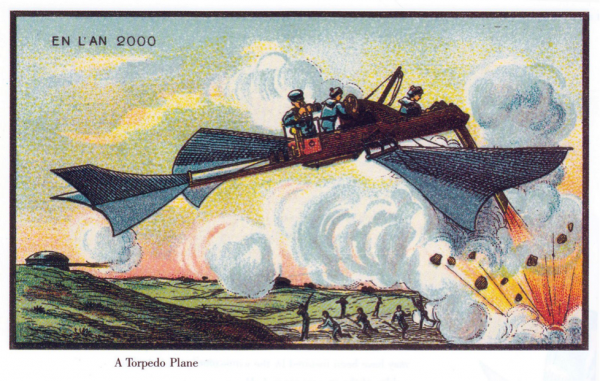

Image from Jean Marc Côté, »En L’An 2000« (1899-1910).

JE: As you completed your Masters of Art with a focus on »ecological futurology and the [im]possibility of a sustainable planet«, an interdisciplinary approach seems to be crucial for your work. What is your interest in science, ecology, its influence on sociology, and possible futures as an artist? Would you consider yourself an activist content-wise?

»Activism has become a form of glorified rejection […]«.Polly Gregson

PG: I’m wary of intellectualizing something as fundamental as ecology by calling it an interest, as it’s too real and too important to be treated like a concept. The term activism is a tricky one for me too. We seem to now be so implicitly involved in harmful systems that the new way to fight it is to opt out. Activism has become a form of glorified rejection, whereby we seek to escape or deny things rather than confront them directly. Not using a mobile phone, not buying from the supermarket, not going on holiday are all seen as forms of resistance, but what exactly are we resisting against if we cannot define a single target? How can we equate these small lifestyle compromises with global revolution? I don’t have the answers to these questions, but elements of my practice aim to stretch out ideas through scenarios or possibilities. If we can imagine conclusions then perhaps we can realize diversions, but then it becomes an issue of defining this »we«.

Image from Jean Marc Côté, »En L’An 2000« (1899-1910).

JE:The topic of the third web residency call »SUPRAINFINIT: L’Avenir redux« was described as the search for other »post-chronological, post-religious-orders-as-we-know-them, post-drugs, post-capital« futures, and formulated quite optimistically with the words: Hope is the new oxygen. Your project draws a kind of dark, dystopian perspective on the future. What was the reason for the decision against a utopian proposal?

PG: If things are already going well, there’s no need for hope.

But not everything in the archive is totally dystopic: there are suggestions to technologies and developments that can exist beyond our current carbon dependency, or of communities that have rebuilt themselves. Paradoxically, we’ve created the concept of utopia, but it can never exist simultaneously with the human race. We’re just too good at fucking things up.

Image from Jean Marc Côté, »En L’An 2000« (1899-1910).

»The world will implode and suck us all into the putrid vacuum before we get a chance to properly develop any of these technologies. Sorry«.Polly Gregson

JE: Taking your research into account, is the scenario depicted in your project a genuine possibility?

PG: No. But only because the world will implode and suck us all into the putrid vacuum before we get a chance to properly develop any of these technologies. Sorry.

JE: A big part of your artistic work is writing. It seems to me as if you are writing with the concept of collection at the back of your mind. Texts appear in very different formats as term definitions from a dictionary, letters, scientific reports or personal notes as if they appeared as found footage like the objects shown in the archive images. What is your approach to text and, concerning this, fiction?

PG: For this project in particular, I wanted the archivist to be an eccentric obsessive, collecting and recording all fragments of this future. A large part of the apocalyptic dialogue is paranoiac and relies on this idea of evidence or proof, where everything holds latent meaning that implies The End. Scraps of writing from different sources compiled in different ways was a way for me to build this hermit persona, emphasizing the levels of self-inflicted craziness such gloomy reflection can throw you into. Fiction’s the light side — we might as well laugh as we trip over our toes and tumble into the abyss.

Image from Jean Marc Côté, »En L’An 2000« (1899-1910).

JE: Do you invent the terms and objects of your archive? What are your sources for inspiration?

PG: Some things stem from literary references, such as Huxley’s »Soma« or food technology from La Nuit Des Temps, but I also owe many ideas to my nihilistic [anti]social circles. Two am conversations about pesticides or pillow-talk that opens with »last night I dreamed the Earth burned again« also mean I’m never far from other people’s dooms. In addition I’ve worked on permaculture farms, community food co-ops, and conservation programs so that’s probably where the strong eco-twist comes from. As for the bleak sociological aspect, current reality provides more than enough material to work with.

»2am conversations about pesticides or pillow-talk that opens with ‘last night I dreamed the Earth burned again’ means I’m never far from other people’s dooms«. Polly Gregson

JE: What does it mean for you to show Future Relics:Catalogue#1 in a digital environment as a web-based work? Does this play a role for the communication/outcome of the project?

PG: The history we’re living now is largely ephemeral. We’re keeping memories, photos, evidence, insights in our tiny SIM cards; huge volumes of information, research and dank memes are uploaded to the internet each second (apparently the total duration of all footage on YouTube now exceeds the age of the Earth) but how are we going to access it later? The computer itself will be an artifact, there will be no way of reaching the data that will perish faster than a disintegrating tapestry because the present has never been so fleeting. I think we’re living in a precarious place with a brittle future, so it seems only right that history should be fragile too.