A sign with the words “Welcome to New Mercy Park” is posted outside a gray institutional building surrounded by deep but calm water. Two years ago, this familiar yet disconcerting place appeared in my dreams. It was so convincingly real that I didn’t even bother to Google it for confirmation when I woke up. New Mercy Park didn’t exist, of course, but I couldn’t get its image out of my head. Something exciting but frightening was happening behind its walls and I had to go see it for myself. Over the following months, my fixation slowly became drafts of a web-based interactive story about biotech, surveillance, and a future prison industrial complex.

"New Mercy Park" in my dream resembled The Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego.

I combined the storytelling idea with a big source of inspiration at the time: “A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer,” the dynamic educational software featured in Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age. The technology described in the book provided the foundations for One Laptop Per Child’s Project Nell, a storytelling device for children that evolves over time with habitual use. The interface eventually prompts its readers to name their own characters, trace over simple shapes, and learn rudimentary letters of the alphabet. The concepts and parables become more complex as well.

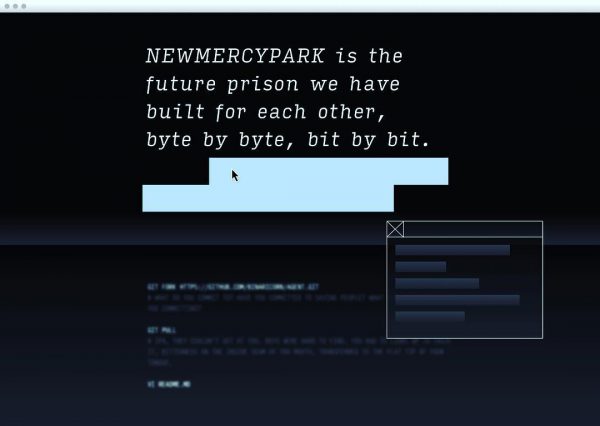

Can writing about code become poetic, sensorial, and evocative? Can the act of following directions and typing commands for learning how to code become as engrossing as reading a good novel? With New Mercy Park, I wanted to show how future networked and nano technology could still be used as “new forms of mercy” to maintain the prison system even if physical ones were abolished. And so I tried to write, but progress was stilted. November 2016 happened and writing a depressing dystopian story while people are activating on the ground and in the streets felt too much like an escape. To echo the sentiments of Morgane Santos, designer and developer of Fantom, about dystopian fiction in 2016 and beyond:

“Whatever dystopian sci-fi hellscape I could come up with, it couldn’t compete with reality. A lot of science fiction assumes the average citizen is living some kind of combative urban nightmare, but most people just like to hang out with friends and eat good food. Why isn’t that part of our vision for the future? What’s wrong with it?” -Morgane Santos

As a designer and artist, my work is critical about the ways technology mediates our interpersonal relationships, but it’s important for me that I am playful and whimsical too.

What hasn’t changed: New Mercy Park is an interactive narrative that teaches coding concepts.

I will use storytelling in physical and digital space, and a combination of games, hands-on workshops, and immersive theater, to make coding concepts easier to understand for artists and designers:

If you know how to code and want to read a story that integrates coding concepts in weird and surprising ways, or if you don’t know how to code and want a weird and surprising way to learn some basics, I want to make that for you.

What’s changed: New Mercy Park is a choose-your-own-adventure story about how social robots and AI will mediate and change our friendships and relationships

I want to hold onto the unease I felt when I awoke from my “New Mercy Park” dream. The world is complicated and most technology is neither all good nor all bad, and take equal turns emancipating and enslaving us. What is “new” and how is it better than the “old” and what does “mercy” and compassion mean when our legal frameworks are one step behind technology, our politics are muddled, and consumerism is driving us to be more individualistic and self-serving? How can I stay true to my perspective on the future and not be led by dystopia’s siren song? These are still questions I am answering as New Mercy Park takes a new direction.